France’s Mediterranean Melting Pot

Located at a gentle curve along the Mediterranean coastline, Marseille has been a thriving port since antiquity. Historically, Marseille was France’s “second city” – the largest in population after the capital, Paris. As various French governments extended France’s imperial ambitions into Africa and Asia, Marseille became increasingly important as the point of entry and exit for goods and peoples moving between empire and metropole. During the 1940s, Marseille’s population fluctuated but typically hovered around 600,000 people who packed themselves in a crowded downtown district or sprawled out in villas overlooking the sea from dramatic cliffs.

Poster by Rodger Border, 1930

Marseille had a famously diverse population, a true Mediterranean melting pot. Migrants streamed into Marseille from all over the world, particularly from countries and regions under the chokehold of French colonialism. In his famous novel Banjo, Claude McKay describes the diversity of “the Ditch,” his name for the area near the docks where migrants and poor workers gathered.

“They were all on the beach, and there were many others besides them —white men, brown men, black men. Finns, Poles, Italians, Slavs, Maltese, Indians, Negroids, African Negroes, West Indian Negroes—deportees from America for violation of the United States immigration laws—afraid and ashamed to go back to their own lands, all dumped down in the great Provençal port, bumming a day’s work, a meal, a drink, existing from hand to mouth, anyhow any way, between box car, tramp ship, bistro, and bordel.” (Banjo)

In this colorful quote, McKay captures the ethnic and racial diversity that characterized Marseille in the late 1940s. But Marseille had long had this multi-ethnic character, especially in the central neighborhoods near Marseille’s tumultuous downtown near the Vieux Port. Sailors poured off ships, migrants disembarked steamers arriving from throughout the French empire and the Mediterranean basin, workers arrived from elsewhere in France, in search of employment, adventure, or a new start. The constant turnover of port life meant that local authorities constantly worried about how to control a population who they saw as transient and lawless. The “underworld” (pègre) of Marseille was constantly discussed in official documents and the municipal government of Marseille looked primarily to the police to control the shifting local population.

Marseille Vieux Port (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

North Africans in Marseille

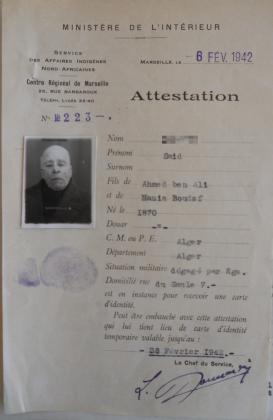

In particular, the police worried about the arrival of North African immigrants. France had colonized Algeria in 1830 (see the Algiers section for more). During World War I, France filled labor shortages in the mainland by recruiting thousands of Algerian workers. Thousands more Algerians were recruited, more or less forcibly, to serve as soldiers in France’s conflict with its European enemies. When the war came to end, the French government tried to send these men back to the colonies. But something had changed. North Africans began an important pattern of circular migration. Mostly men, these North African migrants typically came alone, leaving families behind in North Africa.

Many of the North Africans in Marseille settled in a neighborhood described in police and municipal reports as “behind the Bourse.” This area was so-called because it existed in the shadows of the commanding Stock Exchange building that sat at one corner of the central square near the Vieux Port. The neighborhood “behind the Bourse” was a tangle of narrow streets that twisted up a hill towards the Saint Charles train station. North African migrants were particularly concentrated around Rue des Chapeliers, a short street, almost an alley, dominated by worker’s hostels, cafés maures, and shops selling goods imported from the empire.

Attestation of a North African worker in Marseille.

(Source: Archives départementales des Bouches-du-Rhône, 76 W 206).

By the mid-1930s, the North African population in Marseille hovered in the thousands. The growing number of North African migrants caused concern among police in Marseille. Colonial stereotypes, propagated in official reports, ethnographic studies, and newspaper accounts, described North Africans as violent, crafty thieves, driven by jealousy and pride and naturally inclined to deception. These racist stereotypes had real impacts on the police relationship with North Africans.

Crime in WWII Marseille

World War II shook Marseille to its core. After an initial stalemate at the front, in 1940 Germany staged a new attack and the French army crumbled, almost overnight. The defeated French government agreed to the occupation of Northern France by the German army and a new government, led by World War I hero Maréchal Pétain, was established in the southern spa town of Vichy. Called the Vichy regime, this new government controlled Marseille and the rest of Southern France. Vichy controlled Marseille until August 1944, when the “Free French” forces would liberate the city.

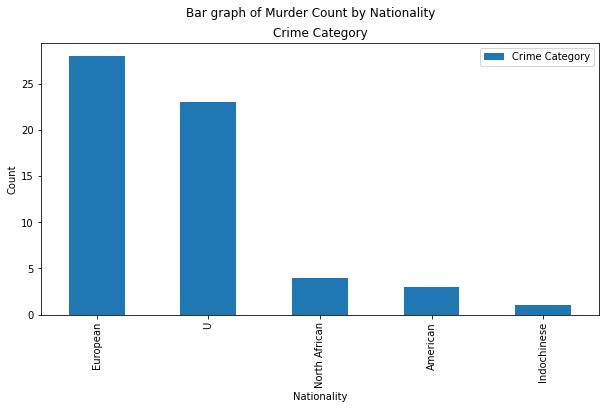

#Work in progress – Need the cleaner version of these two graphs#

As in Algiers, police often described North Africans as key players in the local black market, despite only a few thousand North Africans living in the city. In particular, regular police raids on the area around Rue des Chapeliers, the central hub of North African life, reveal a concentration on North Africans in police goals of repression. Though overwhelmingly Europeans committed Black Market crimes in Marseille, North Africans are still over-represented in these figures.

A similar pattern can be seen for the relative rates of reports on Illegal Arms possession and assault, both crimes associated by police with the supposedly “passionate” and “violent” nature of North Africans.

Most murders in Marseille were committed by unknown aggressors and often went unsolved, as indicated by the relatively low rates of arrests v. reports for this crime. Marseille, sometimes called the “Chicago of France,” had a reputation for being violent and dangerous, a reputation enhanced by famous detective novels set in the city. Despite this imaginary, however, the numbers here seem to indicate a relatively low rate of murder, as compared for example, to Algiers.

Vagrancy charges were frequently leveled against North Africans, as a tool to control their movement and also their labor. But given that this data comes from immediately after WWII, many arrests of North Africans are likely not represented because of military efforts to control North African labor and movement, which would not have been recorded in daily police reports

These graphs reveal telling patterns in Marseille. Predominately, those accused of or arrested for crimes in Marseille were European. But this makes sense in a city where the European population made up the vast majority of the population. Yet, North Africans are also omnipresent in this dataset, despite only a few thousand North Africans living in Marseille, a city whose population hovered around 600,000 people in this period. The daily police reports that this data comes from do not and cannot tell us about the nature of crime in Marseille in 1946. What it can tell us is what the police did. As these arrest records show, police disproportionately targeted North Africans in their mission of repression, particularly in crimes like theft, fraud, violent assault, and the black market. These crimes are precisely those that official reports, ethnographic studies, and contemporary French newspaper articles tended to identify as particularly “Arab” vices. These racist stereotypes had real influence, forming a picture of the “usual suspects” that influenced daily police patrols. Even though North Africans were a relatively small portion of the population in Marseille, they were nonetheless targeted by police officers in Marseille.

Further Reading: